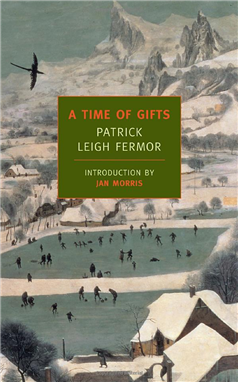

In December 1933, nineteen-year-old Patrick Leigh Fermor set out alone on a great adventure, a walking trip from Amsterdam to Istanbul, or as Fermor still called it, Constantinople. (It was renamed in 1930.) He had no idea when he left that he would not return until 1937. In 1977, he collected his notebooks from the trip and wrote A Time of Gifts and its sequel Between the Woods and the Water.

In December 1933, nineteen-year-old Patrick Leigh Fermor set out alone on a great adventure, a walking trip from Amsterdam to Istanbul, or as Fermor still called it, Constantinople. (It was renamed in 1930.) He had no idea when he left that he would not return until 1937. In 1977, he collected his notebooks from the trip and wrote A Time of Gifts and its sequel Between the Woods and the Water.

Although Leigh Fermor had one notebook stolen from him with all the rest of his gear, he otherwise must have kept careful account and his memories of the trip must still have been vivid, for the result is an entrancing account of scenery and architecture, tales of chance encounters, glimpses of foreign customs and celebrations, and so on. Jan Morris, who wrote the introduction, calls him “one of the great prose stylists of our time,” and Wikipedia, quoting an unnamed British journalist, “a cross between Indiana Jones, James Bond and Graham Greene,” presumably for his work with the Cretan resistance in World War II as well as his writing. (He was also a friend of Ian Fleming.)

From his drinking bouts with Dutch barge men to his extended stays in various German, Austrian, and Czech castles, Leigh Fermor plunges enthusiastically into every experience on offer. At one moment he is sleeping in a barn, in the next hanging out with fashionable youth in Vienna. Along the banks of the Danube he is mistaken for a 50-year-old smuggler. All of these adventures as well as his observations of nature are described in beautiful, evocative prose. To add interest to the modern reader, he is describing a Europe that no longer exists.

If I have any complaint, it is one of my own education, for Leigh Fermor’s writing assumes for his audience a familiarity with classical culture that is no longer common. The book often alludes to mythology and refers to obscure historical events that I do not fully understand. Finally, in the footnotes, which are Leigh Fermor’s original ones, all utterances in modern languages (some of which I could have taken a stab at) are translated, but the quotations in Latin are not. They are not integral to comprehension, but it is a little frustrating to be unable to understand them. (Of course, I could have googled them, but I was almost always reading this on the bus.) That being said, I look forward to reading the sequel.