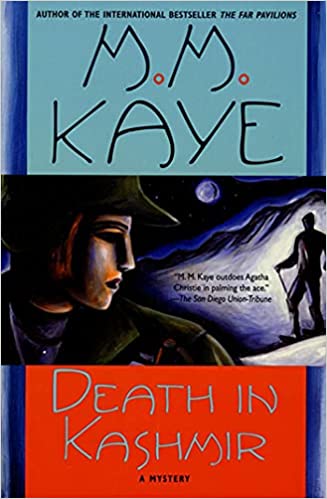

A quote on the cover of Death in Kashmir compares M. M. Kaye to Agatha Christie. A more accurate comparison in terms of the type of novel it is—romantic suspense rather than mystery—is to Mary Stewart, although there is just something about a Mary Stewart book that this novel doesn’t quite have. Still, Death in Kashmir is entertaining enough.

The novel is set in 1947, the year before the British left India, and it provides an interesting look at the life of British upper-class people living there at the time, although the natives are mostly only in the book as servants.

Sarah Parrish goes to Kashmir to attend the last meeting of the India Ski Club at Gulmarg in a primitive hotel that is usually only open in the summer. The outing has already been shadowed by the death that day of Mrs. Matthews in an apparent skiing accident. In the middle of the night, Sarah awakens to a scraping noise and realizes someone is trying to break into the room next door, that of another young woman, Janet Rushton. Sarah quietly hurries to Janet’s door to warn her and is shocked to be greeted by a drawn gun. However, when Janet sees someone has tried to enter by the bathroom window, she confides in Sarah that she is an agent for the government. She and Mrs. Matthews discovered an important secret and were waiting for help from their superiors when Mrs. Matthews was murdered.

A few nights later, Sarah and Janet have joined an expedition farther up the mountain to ski and spend the night in a ski hut. Sarah catches Janet ready to ski off in the middle of the night because she has finally been contacted by her people. The next day, she too is found dead.

Returning to Peshawar after the trip, Sarah tries to forget what she has learned, but she receives a letter from Janet’s attorney enclosing the receipt for her houseboat in Srinagar and telling her the secret can be found there. So, she finds herself returning to Kashmir with her friends Hugo and Fudge Creed. There she encounters all of the people who were on the ski trip, with a few extras, like the attractive Captain Charles Mallory.

The Cold War plot seems a little silly when compared to those of some of the masters, like Le Carré (and may more fairly earn the comparison to Christie, who also has some silly Cold War plots), but it leads to plenty of suspense and an unguessable villain. A small criticism is that both sides seem to have so many helpers that it’s no wonder there was a leak. A bigger caveat is that the explanations at the end go on for quite a while longer than seemed necessary.