Since I have posted my last review of the shortlisted books for the Booker Prize of 2019, it’s time for my feature where I decide whether the judges got it right. The nominees for that year include a dystopian novel, several novels that experiment in form and two that experiment in narrative style, and one fantasy/satire.

I often start this post with the books I liked least, but in this case, I have a little problem with that, and that is to decide which ones I disliked the least. In fact, on the list for this year, there are none that I thought were entirely successful and several that I actively disliked.

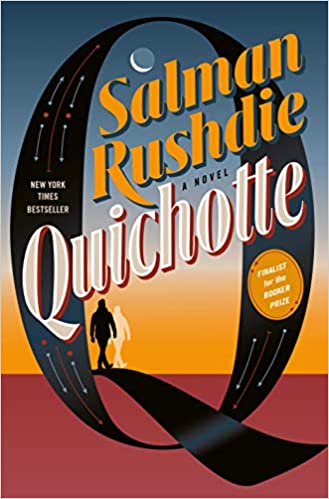

So, I’ll start with the one that is freshest in my mind, Quichotte by Salman Rushdie. This fantasy/satire about an elderly man on a road trip (that doesn’t get anywhere) with his imaginary son was a DNF for me. I felt Rushdie constantly winking at me as he proceeded with his ponderous humor that wasn’t funny at all.

The other novel I disliked intensely was An Orchestra of Minorities by Chigozie Obiama. I thought this novel, about a man who will supposedly do anything for love, was riddled with sexism and outright hatred of women. Its hints of Igbo culture are interesting, but also slowed down the forward impetus of the novel.

Now, we get to the novels that I thought were ambitious but not quite successful. Elif Shafak’s 10 Minutes 38 Seconds in This Strange World tackles violence toward women in an unusual way, but I found its change in tone to be jarring. In addition, the concept of the first part of the novel, which represents the 10 minutes and 38 seconds of brain activity in a dying person in 200 pages (short period of time, long time of reading), just didn’t work for me.

Ducks, Newburyport by Lucy Ellman was experimental by anyone’s reckoning. This novel, which is basically one 1000-page sentence (except for a few intervals that are written normally) broke every rule about writing I can think of. It was oddly compelling, enough to make me finish, but I’m not sure it provided much payoff for all the effort.

I didn’t actually say this in my review of The Testaments, but I really felt it was a bit of a sell-out by Margaret Atwood, only written to satisfy the fans of The Handmaid’s Tale television series. I felt it very conveniently wrapped things up and was far less of a landmark book than her original novel. It was also the most traditionally written book of the shortlisted novels for 2019. However, it was Atwood, so it was compelling reading.

That brings us to Girl, Woman, Other by Bernardine Evaristo, a cowinner of the award with The Testaments. This novel of linked short stories about women is also experimental in form, having hardly any periods. I called it a semi-successful experiment in form and writing style, but it did include some powerful stories. In a year that was hard to pick favorites, I guess this would be my pick. Since this novel was a cowinner of the award, I guess that makes the judges half right.