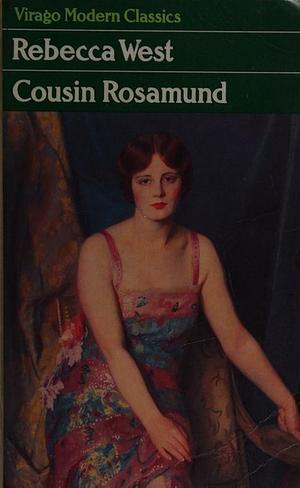

Cousin Rosamund is the third book in West’s Aubrey family series, and another was planned. I couldn’t tell when reading it, but apparently West died before finishing the second book, This Real Night, so it was finished from fragments and notes. Cousin Rosamund was assembled the same way, although West’s style was certainly captured.

The novel begins sometime after World War I. The three Aubrey girls, Rose, Mary, and Cordelia, are the only ones left of their immediate family, but they still have Nancy, their old neighbor; their beloved cousin Rosamund; and the folks at the pub on the river. Cordelia, always the odd girl out, has become less hostile since her marriage.

Cousin Rosamund comes to tell Rose and Mary that Nancy is getting married. Mary especially is upset that Nancy didn’t tell her herself, but Rosamund’s intercession, they see later, is needed so that they will not judge Oswald on sight, for he is gauche, awkward, unattractive, and a man-‘splainer. But he loves Nancy and she him, and that is all that counts.

Rose and Mary are now both successful and famous pianists, but neither is interested in marriage. Mary, in fact, seems to find the idea distasteful, although they are glad to see their friends happily married.

Inexplicably, Rosamund, who has been working as a nurse, marries one of her patients. The girls are all hurt not to be invited to the wedding, and once they meet the groom, they are horrified. His name is Nestor Ganymedios, and he is rich, extremely vulgar, ugly, and probably dishonest in his business dealings. Further, they see almost nothing of her after the marriage.

This novel is about marriage, which West examines in several incarnations. Unfortunately, it ends before we learn the explanation for Rosamund’s choice, but at least West’s intentions for the entire series are explained in the Afterword of my Penguin edition.

All of these novels are beautifully written and show a profound knowledge of music. The girls have such pure affection for the small number of people they love, yet the characters are realistically drawn.

One caveat: In this novel some characters express outdated ideas about homosexuality, and some homosexual characters in the book are not depicted positively, but it is not clear when she wrote this. The first book went to the publishers in 1956, at which point she said she planned three more, but though she finished most of the second, she seemed unable to finish this one. It ends about 1929, but her original plans were to encompass World War II.

Although it doesn’t fit the context of what I’ve discussed, I wanted to give just one quote because it’s so lucid and poetically spare. Rose has seemingly been disgusted with her long-time friend Oliver after he told her the story of his first marriage despite its end not being his fault. She is really fighting a battle with herself. She enters a room where he is.

He came toward me and I became rigid with disgust, it seemed certain that I must die when he touched me, but instead, of course, I lived.

Wow.