Today is another review for the Literary Wives blogging club, in which we discuss the depiction of wives in fiction. If you have read the book, please participate by leaving comments on any of our blogs.

We also welcome another member to our group! Becky Chapman is a new member from Australia. You can see her bio on my Literary Wives page. Welcome, Becky!

Be sure to read the reviews and comments of the other wives!

My Review

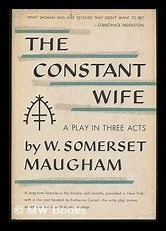

The Constant Wife is a play by Maugham, a social comedy that is reminiscent of one of Wilde’s. It is witty and reflects some interesting attitudes about marriage and faithfulness. It is set completely in Constance Middleton’s drawing room.

The play begins with the revelation that most of Constance’s friends and relatives think her husband John is being unfaithful with her best friend, Marie-Louise Durham. Constance’s sister Martha wants to tell her, but her mother, Mrs. Culver, does not. In any case, once the matter is hinted at, Constance refuses to hear and says she is sure John is faithful to her.

John and Marie-Louise are having an affair, though, and it turns out Constance knows. She has been maintaining the status quo, but when the truth comes out, it turns out she has some unusual ideas about marriage, especially for the time. At the same time, Bernard, a former suitor of Constance’s, returns from years in China.

The play is meant as a light diversion, I think, but its ending was probably considered pleasantly shocking at the time.

I try hard not to judge works out of their time, but although the script is undoubtedly witty, it reflects some attitudes that made me wince. Here’s one that seemed so strange it was funny. I’m not sure what early 20th century British people of a certain class thought feminism was, but in an early speech Mrs. Culver says she told a friend whose husband was unfaithful that it was her fault because she wasn’t attractive enough. (Ouch! But that idea was still around when I was growing up.) What made me laugh, although I don’t think it was meant to be funny, was that Constance in response asks her if she’s not “what they call a feminist.” Maybe it was meant to be funny. Hmm.

What does this book say about wives or about the experience of being a wife?

I think a discussion of this topic probably involves spoilers, which I try to avoid. But here goes.

This play comments in several ways about marriage and fidelity. First, there is the idea that it’s okay and expected for a man to cheat, expressed by Mrs. Culver. The corollary to that is that it is not okay for the wife. Martha does not agree. She thinks both should be faithful. Constance’s attitudes are more complex.

At first, Constance wants to maintain the status quo of her marriage by ignoring the situation. Then when she is forced to acknowledge her husband’s infidelity, she does and says some surprising things. She is very matter of fact about it and expresses the idea that they were lucky because they both fell out of love at the same time. John, more conventionally, affects to love her still.

Constance has been offered a place with a successful decorating business by her friend Barbara, which she originally turned down. Now, she decides to take it, eventually explaining that John’s rights over her have to do with him supporting her, so she wants to be independent. And a year later, there is more to come.

I’m not sure whether Maugham was making serious points about marriage and the relationships between the sexes or just trying to shock and be funny. The upshot of the play is what’s good for the goose is good for the gander—or the other way around.

There are still lots of implicit messages in the play:

- That women are still property, based on their being supported by men. And Constance discounts running a house and caring for children as if it were nothing

- That once love has calmed, marriage is basically a financial arrangement

- That women are more interesting when they’re unobtainable than when they are present and faithful

These are the women’s attitudes, mind you (although I keep reminding myself that this play is written by a man). John isn’t that much heard from, except his cowardly request for Constance to break up with Marie-Louise for him and his conventional assertions that he still loves Constance.

Related Posts

All’s Well That Ends Well

The World’s Wife

Excellent Women