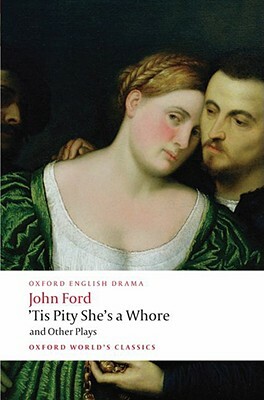

I have to admit I picked this play for my Classics Club list because knowledge of the plot was a major clue in the first Midsomer book, The Killings at Badger’s Drift. A clue that I missed.

John Ford was a playwright in the Jacobean and Caroline eras. Really nothing is known about him, and although I took a graduate course in drama that started with Christopher Marlowe and included Jonson, Kidd, Webster, and Tourneur, he was never mentioned. He was a famous playwright during the reign of Charles I, and his plays usually deal with the tension between passion and the laws of society. ‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore is his best-known play, and despite its subject matter, it is regarded as a classic of English literature.

And this is truly a gruesome play, with few redeeming characters. The drama is around a situation that evolves immediately in Act I. Arabella is a beauty of Parma who is courted by several noblemen. But it is Giovanni, her own brother, who wins her, and their relationship is consummated at the end of Act I. Spicy stuff!

Arabella is being courted by Soranto, but he has his own drama. He once seduced Hippolyta with promises of marriage if her husband died. Her husband now lost and believed to be dead, her reputation is ruined for nothing, because Soranto has dropped her. When she confronts him, he calls her a few bad names. She wants her revenge, and Vasquez, Soranto’s Iago-like servant, pretends to be sympathetic only to learn her plans.

As could be expected but apparently isn’t, Arabella finds herself in a situation where she has to get married. She reluctantly agrees to marry Soranto.

Interestingly, we seem to be expected to sympathize with Arabella and Giovanni. Certainly, there aren’t any other nicer characters. The Cardinal favors a Roman nobleman after he murders a man, and the Priest, who has been Giovanni’s confidante, runs away when things get dicey. Arabella’s governess apparently sees nothing wrong in her having an affair with her brother.

No one goes unpunished, but the fate of the women is much more gruesome than that of the men.

I thought the play was surprisingly readable and went very quickly. It doesn’t have beautiful speeches like Shakespeare, but it is partially in verse. I am sure its audiences found it very exciting.