I don’t usually post on Saturdays, but I had one more book that I read for the 1954 Club.

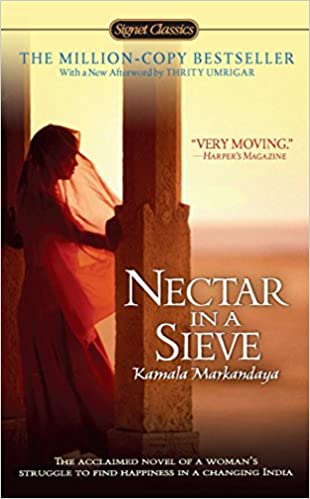

When I saw that Nectar in a Sieve qualified for the 1954 Club, I was excited to read this landmark novel. It depicts the life of poor Indian peasants, and as the Afterword of my Signet Classics edition states, nothing much has changed for them in the 80 years since it was written.

As the daughter of the village headman, Rukmani might have expected a more memorable wedding, but she is the youngest daughter, so no dowry was forthcoming and she is plain. So, Rukmani is married at the age of twelve to a poor rice farmer, Nathan, who does not even own his own land. But, she thinks as an old woman recollecting her life, her parents made a good choice, for Nathan was good and kind.

Rukmani remembers her life, a precarious one where they were never able to afford to buy the land, where one misfortune could mean disaster—and they had several.

Rukmani thinks things start to go wrong with the arrival of the tannery, which turns their village into a town and brings in many strangers. But one year of flood followed by one of drought cause starvation and worse problems when Rukmani and Nathan are middle-aged.

By coincidence, just before I read this novel, I read The Year of the Runaways by Sunjeev Sahota, about the life of Indian illegal immigrants in London. In all these years, nothing much seems to have changed except the ultimate outcome.

In some ways, Nectar in a Sieve is more like social reporting than a character- or plot-driven novel. The only character we really get to know is Rukmani herself. However, the novel is poetically written and tells a powerful story.