Today is another review for the Literary Wives blogging club, in which we discuss the depiction of wives in fiction. If you have read the book, please participate by leaving comments on any of our blogs.

Be sure to read the reviews and comments of the other wives!

- Lynn of Smoke and Mirrors

- Naomi of Consumed By Ink

- Rebecca of Bookish Beck

My Review

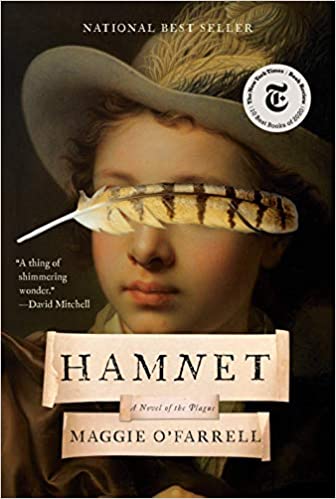

Hamnet is a reread for me for Literary Wives, so if you would like to revisit my original review, including the synopsis of the plot, it’s at this link. Let me also comment that it was one of my Top Ten Books two years ago.

What does this book say about wives or about the experience of being a wife?

There are several reasons why people assume that William Shakespeare’s marriage to Anne Hathaway (whom O’Farrell calls Agnes) was not a happy one. She was several years older than he and pregnant when they married; they lived apart most of the time; he left her his second-best bed (which is misunderstood). But Maggie O’Farrell chooses to take another point of view, that it was a love match.

The novel alternates chapters between the history of their relationship and their son Hamnet’s last days. Then it switches gears to show the aftermath of his death. By the way, Shakespeare is never mentioned by name.

In this novel, Agnes is a wise woman who knows all the healing herbs and can see into a person’s mind by grasping the muscle between their thumb and forefinger. She is thought to be strange and a witch. When she grasps Will’s hand for the first time, she sees vastness.

But Will has a hostile relationshp with his father and dreams of other things than being a glover. When he becomes depressed because he has no work, Agnes puts her head together with her brother Bartholomew, who suggests he be sent to London to sell gloves for his father. Will soon finds his element in London and plans to move the family there when he can afford it. But because of Judith’s poor health, the family can’t follow him there.

But the novel sticks at home, where he visits when he can, sometimes as long as a month—until Hamnet dies.

The novel depicts an Agnes otherworldly but confident in her relationship with Will until Hamlet’s death creates a break. Her grief is so excessive and he can’t bear to be reminded of his son, while she wants only to remember him.

This novel paints a moving depiction of grief and of how Shakespeare’s play eventually creates a mutual understanding. It’s a powerful novel, and there is probably a lot more to say about it, but I find myself unable to convey much more.