I know I’m early in reviewing my Classics Club Spin book, but it just so happens that when it was picked for the spin, I had just read it but not reviewed it yet. Lucky for me, because so many of the books remaining on my list are really long!

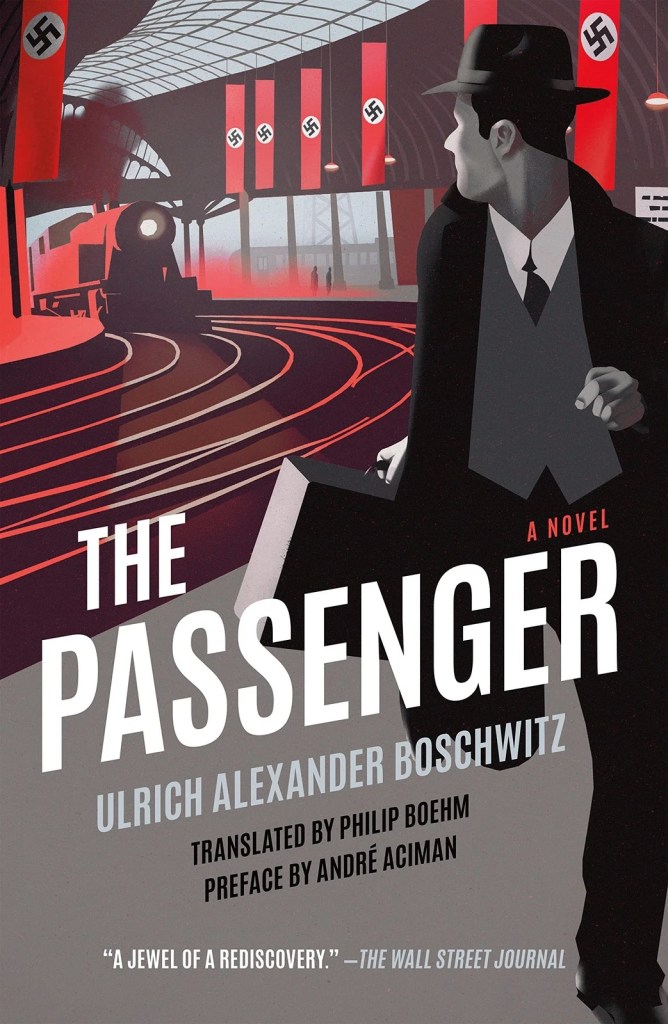

I am not sure how The Passenger made it onto my Classics Club list, but its origins are certainly interesting. Boschwitz, who had already escaped Germany with his mother, was so affected by the events of Kristallnacht that he wrote this novel in a great hurry. It was published in England in 1939 and in the U. S. in 1940, but then it just vanished. Revisions he mailed to his mother never arrived. Then, in 1942, he and his manuscript were on a passenger ship that was torpedoed by a German U-boat, and they were lost. Nearly 80 years later, a correspondence with Reuella Shachaf, Boschwitz’s niece, mentioned to Peter Graf that the manuscript for the book was held in an archive of the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek. So Graf looked it up and helped edit it and get it republished. It came back out in 2018.

The book opens with wealthy Jewish businessman Otto Silbermann handing over 51% of his business to a friend, Becker, to save it from being taken. As Becker points out, there is nothing Silbermann can do about it because he’s Jewish. Jewish men are being rounded up, but Silbermann has an advantage of not looking Jewish.

Back at home with his Christian wife, he tries to sell his house to another friend, Findler, who cheats him. Again, there is nothing he can do about it. Then thugs begin pounding on the front door, so Findler sends him out the back, saying he’ll protect Elfrieda.

Silbermann begins a journey lasting days, traveling by train from one city to another to find a way to escape Germany. His goal is to go to his son Eduardo in Paris. But Eduardo has been unable to get him the papers he needs. In the meantime, he lives in a state of paranoia, listening to constant insults to Jews, fearing strangers, and thinking he’ll be arrested any minute.

This is a tense novel that seems very realistic, although Silbermann occasionally becomes incandescent with anger about the injustice, thereby risking his own life. It’s a compelling novel.