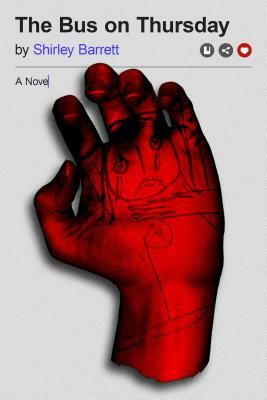

Well, this is certainly a strange book. It has been billed as a horror novel, but I think that’s misleading.

Eleanor Millet begins her story, which is related as blog entries, in a bad place. She is recovering from breast cancer after a mastectomy. She has lost her boyfriend and her job and has had to return to live with her mother. She is angry and outspoken and pretty darn funny, but we notice right away that she has poor taste in friends and men.

Her description of the path her cancer diagnosis took grabbed me right away, because last year I was called back (which in itself is fairly terrifying) for first an ultrasound mammogram and then two, count ’em, two biopsies. Luckily, I was okay, but Eleanor was not.

Now Eleanor can perhaps turn her life around. She gets her dream job—a teaching position in a very small town in the Snowy Mountains. But already she seems to be behaving a little off-kilter.

Eleanor is urgently needed because the previous teacher, Miss Barker, has disappeared without a trace. The school staff are Eleanor and Glenda, the school secretary, and the school holds all of the town elementary and middle school students up to age 14, with one boy, Ryan, who seems suspiciously older. Glenda behaves as if Eleanor has committed a crime by taking Miss Barker’s place, and Eleanor’s home used to be Miss Barker’s and has a lot of locks on the doors.

Things start out strange, with people treating Eleanor in an oddly hostile way, and two people telling her that her cancer was her own fault. The local minister tells her she had cancer because she is possessed by a demon.

This is all very strange, but Eleanor’s reactions are over the top, and she almost immediately begins drinking too much, having an inappropriate relationship with one of her students’ guardians, and behaving inappropriately with her students. She starts having bizarre dreams and soon we’re wondering about her reliability as narrator, even her sanity.

I am a critic of book blurbs, and the one on the back of my book seems particularly misleading, speaking of a “portrait of recovery and self-discovery.” Things are a lot darker than that.