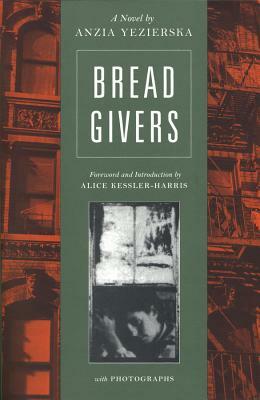

The last book I selected for the 1925 Club is Bread Givers. It is the mostly autobiographical novel about poor Jewish immigrants living in New York.

The novel opens with the Smolinsky family not having enough money for the rent. Reb Smolinsky spends all of his time studying the Torah and depends on his wife and daughters to support him. Bessie, the oldest daughter, earns the most and willingly hands over every penny to her family, but she is getting a little old to attract a husband. Mashah, the beautiful next sister, takes all her money to spend on finery, buying a new trinket when her family doesn’t have enough money to eat. Fania, the third sister, is still fairly young. Sara, the narrator, is only ten, but she goes out to buy some herring and then sells it on the street for twice as much, coming back with the rent and enough for some food. The father, of course, gets all the good parts of the food and any meat. After this incident, the family takes in lodgers and begins to do better.

Sara begins to form her own opinion of her father and their lives through the experiences of her mother and sisters. Her father takes any extra money for his charities and clubs, so her mother never has anything nice.

Bessie gets a boyfriend. Berel Bernstein is a hard-working tailor who plans to open his own shop and wants to marry Bessie because she is a hard worker and will make a good wife. So, he is willing to overlook the absence of a dowry. But their father tells Berel he wants money from him to make up for losing Bessie’s wages. He says he must have new clothes for the wedding, never mentioning a dress for Bessie. Berel doesn’t accept this or their father’s hostile attitude and leaves angrily. Weeks later, Bessie hears he is engaged to another girl. The light goes out of her.

Then Mashah begins to behave in a less selfish way. It turns out she is in love, with concert pianist Jacob Novak. Jacob is supported by a wealthy father, and when Mr. Novak comes to meet the family, it’s clear that he views them like dirt under his feet. Jacob doesn’t have the courage to stand up to him. He eventually returns, but Mashah has lost her faith in him and in love, so she sends him away.

Then Fania falls in love with Morris Lipkin, a journalist and poet. But the holy Reb Smolinsky thinks Lipkin isn’t good enough. After a big argument with his family about how he’s been driving off his daughters’ suitors, he claims he can find them better husbands. He brings home a flashy diamond merchant on the night Lipkin comes to ask for Fania in marriage and ignores Lipkin, who then leaves.

Like everything her father does, his matches end in unhappiness for his daughters. Sara begins to hate him and decides her life will not depend on a man. She is working in a box factory, but she decides she is going to college to become a teacher. And at every step she has to navigate a different foreign culture.

Written in the vernacular, this novel is a personal story of struggle against poverty and ignorance. Of course, Sara’s family think that education isn’t for women, but only submission to a husband is. I found this work really gripping. I read it in one day. My Persea Books edition is illustrated by photos from a film based on Yezierska’s short stories.