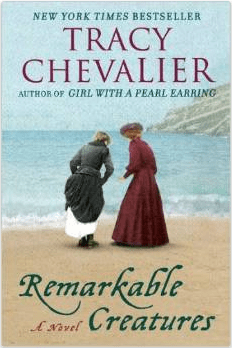

Best Book of the Week!

Best Book of the Week!

In 1885, Cora Seabourne is a recent widow and is happy to be so, as her husband abused her. For the first time, she feels free and is not eager to remarry, even though surgeon Dr. Luke Garrett is in love with her.

Cora is interested in fossils and has made a heroine of the early fossil finder Mary Anning, so she moves with her son Frankie and her friend Martha to Essex, where she can explore the sea coast. Soon after arriving, she hears rumors of the Essex serpent, a monster that has been supposedly terrorizing the area. There are rumors of slain farm animals and lost children. Cora hopes to find a living prehistoric animal. The villagers are more superstitious, and an aura of dread soon develops.

Cora finds happiness rambling around the countryside, so she delays introducing herself to the Ambroses, Reverend William and his wife Stella. But when she finally meets them, they become fast friends. In particular, Will and Cora enjoy debating such subjects as science versus religion, a topic made even more controversial since Darwin’s discoveries. Sadly, it soon becomes obvious that Stella has tuberculosis.

This novel evokes the ideas and preoccupations of the Victorian age. Although it has quite a few characters, they are all convincingly portrayed. I was deeply interested in the novel. It presents a fully realized world, vividly imagined and described.