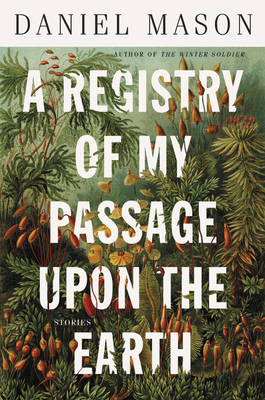

A Registry of My Passage upon the Earth is a collection of short stories that I read for my Pulitzer Prize project. I sometimes have problems reading short stories, but I found most of these engrossing. Most of them were about scientific curiosity and the characters’ actual or potential legacy.

“Death of the Pugilist, or the Famous Battle of Jacob Burke & Blindman McGraw” is set during the early 19th century. It is about how a burly lad becomes a prize fighter. These were the days of no-holds-barred bare-knuckle fights.

Another historical story, “The Ecstasy of Alfred Russel Wallace,” is about an early collector of bug specimens who begins to draw conclusions similar to Darwin’s about the survival of the fittest. He writes to Darwin hoping for a scholarly exchange, but perhaps Darwin is worried about which of them thought of the theory first. This one has really beautiful prose.

“For the Union Dead” is a contemporary story about the narrator’s uncle, who became involved in Civil War re-enactments.

“The Second Doctor Service” is a letter to a medical journal from a 19th century man who begins having periods of blackouts and thinks another self is trying to take him over.

“The Miraculous Discovery of Psammetichus I” is based on a story by Herodotus. It’s a series of descriptions of experiments supposedly performed by a curious Pharoah, most of which involve having children raised by animals.

“On Growing Ferns and Other Plants in Glass Cases, in the Midst of the Smoke of London” is set in the 19th century during the height of the industrial revolution and major air pollution. A widow’s young son begins suffering from severe asthma, and the doctors fail to treat it successfully. She eventually gets a better idea.

“The Line Agent Pascal” is set in the 19th century South American jungle. Pascal is a telegraph operator who likes the isolation of his position but forms a sort of family with the other operators. There is one in particular whom he has never met but for whom he feels an affinity.

“On the Cause of Winds and Waves, &c” is a letter to her sister by a 19th century balloonist in France. Observing a strange phenomenon in the heavens, she is asked to report about it to the scientific Académie, but she doesn’t realize she has only been asked to be ridiculed.

“A Registry of My Passage upon the Earth” is a record by a man who has been incarcerated in an insane asylum but is probably OCD or on the spectrum instead of insane.

Most of these stories have some kind of uplifting ending. Maybe I enjoyed them so much because many of them felt like short historical novels. I liked them a lot.