Twice a year, Simon of Stuck in a Book and Kaggsy of Kaggsy’s Bookish Ramblings host a year club, and this October the year is 1925. For this club, participants read a few books from that year and all post their reviews on the same week. Just by coincidence, this year the books also qualify for Neeru’s Hundred Years Hence Club.

Previous Books from 1925

As usual for my first post for the year club, I’ll start out by listing books I have already read for that year with links to my reviews, if I read them while blogging:

- The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

- No More Parades by Ford Maddox Ford

- Greenery Street by Denis Mackail

- Giants in the Earth by Ole Rølvaag

- Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woolf

- William by E. H. Young

My Review

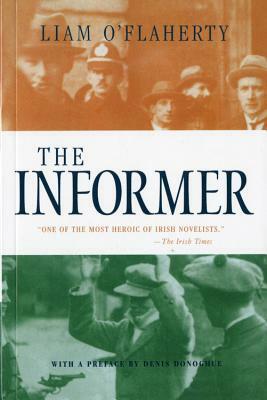

I picked The Informer for the 1925 Club without knowing anything about it or about Liam O’Flaherty. It was a winner of the James Tait Black award, written in the style of Naturalism and set after the Irish Civil War.

Francis Joseph McPhillip is a wanted man. He was a member of the Revolutionary Organization when he murdered the president of the Farmer’s Union during a strike. He and his friend, Gypo Nolan, were booted out of the Organization as a result, and Frankie has been on the run with a price on his head. But he has become tired of running and has returned to Dublin. The first thing he does is search out Gypo to ask if his parents’ house is being watched, and then he goes home.

Gypo is a brute—huge, strong, ugly, and very stupid. He has always done what Frankie told him to do. But ever since he got thrown out of the Organization, he can’t get work. He has no home, and no one will help him. He doesn’t have anywhere to sleep that night. He gets an idea. If he turns Frankie in to the police, he’ll have the reward money. So, he does.

The word is soon out that Frankie is dead, shot by the police at his parents’ home. Being an idiot, Gypo is running around town spending money on liquor and women. He just manages to come up with a story that he robbed an American sailor.

Even as an ex-member of the Organization, Frankie is still in its sights, as it is clear someone informed against him. Commandant Dan Gallagher is already looking at Gypo, because Frankie told his parents he had seen Gypo. Gypo is not very good at thinking, but he makes up a story that he saw Rat Mulligan skulking after Frankie in the street. But Rat has an alibi.

Naturalism isn’t my thing, and true to the literary movement, many of these characters are the dregs of society. It’s hard to empathize with a stupid fool who turns in his friend for a few bucks. Other characters are mostly street people—hookers, addicts, and so on—and those in the Organization who have a philosophy spit out half-digested rhetoric. Also, the ending of the book is over the top. A powerful book in its time, but not my thing.