Announcement of a Review-Along!

Before I plunge into my topic, FictionFan and I are announcing a Review-Along of the works of Henrik Pontoppidan, the Danish Nobel Prize for Literature winner (1917). We both chose his most famous book to read, A Fortunate Man (also known as Lucky Per), but readers are welcome to choose any of his works that are available. We’re aiming for March, as A Fortunate Man is a real doorstopper! See the details at FictionFan’s announcement post here!

James Tait Black Fiction Prize Wrap-Up

A few years ago, I decided to add the James Tait Black Fiction Prize to my shortlist projects. However, after a while I felt like I was reading too much British fiction as opposed to American or fiction from other countries, since all my prize projects were Brit-based and I also read a lot of reprinted British fiction. So, I dropped the James Tait in 2023 and added the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. For the James Tait, I started my list back a few years, at 2010.

When I was just trying to wrap up this project by finishing the few books I had left to read, some fellow bloggers asked me if I would provide a wrap-up post for my reading. So, here it is, for the shortlisted books from 2010-2023, I know I’m finishing a few years later, but many of the books for this project were never available from my library, so I waited to see if they would become available and at the end, had to buy them. That hasn’t been a problem with my Booker or Pulitzer projects, although it has sometimes affected my Walter Scott Fiction Prize project.

The Data

Thanks to a request by FictionFan, I am providing data about my project. I am not a data person, so bear with me.

I began this project October 6, 2017, and decided to wrap it up in 2023. I finished reading on October 4, 2025, but it’s taken me this long to schedule the final two reviews. I posted my last review last Thursday, November 20, 2025.

Number of books read for project: 57

Ratings in The StoryGraph

Keep in mind that until 2025, I stored this data in Goodreads, which does not allow fractional ratings. There were only two books in the list that had fractional ratings, so I rounded them down. I am not really happy with 1-5 ratings, because to me, a 3.25 rating (a little bit better than 3, which is my meh rating), for example, is a lot different than a 3.75 rating (almost a 4).

Yes, I made some charts! It’s been a long time since I used Excel, so pardon me for any awkwardness. As you can see below, most of the books were rated either 3 (green) or 4 (blue).

Author Information

Number of female authors: 34; Number of male authors: 22

Note that one author made the shortlist twice.

I made a chart for author nationality. This chart is off by one because Sarah Hall is listed twice in my data, and I couldn’t figure out how to exclude one of her from this chart. So, there is one extra count for “English.” I used nationality as listed in Wikipedia, which for some authors listed two. Where are the Canadian authors, guys?

Settings

This answer was difficult, because some settings were unspecified while other books were set in several places, and one was just “Europe.” The chart I generated was unpleasing, so here is the data entered by hand for number of books in a setting:

U. S.: 17

England: 13

Ireland: 2

Scotland: 2

Multiple countries: 9

Unspecified: 5

Only one novel is set in each of the following countries: Kosovo, Bulgaria, Italy, Spain, Nigeria, Russia, Japan, Uganda, and Vietnam.

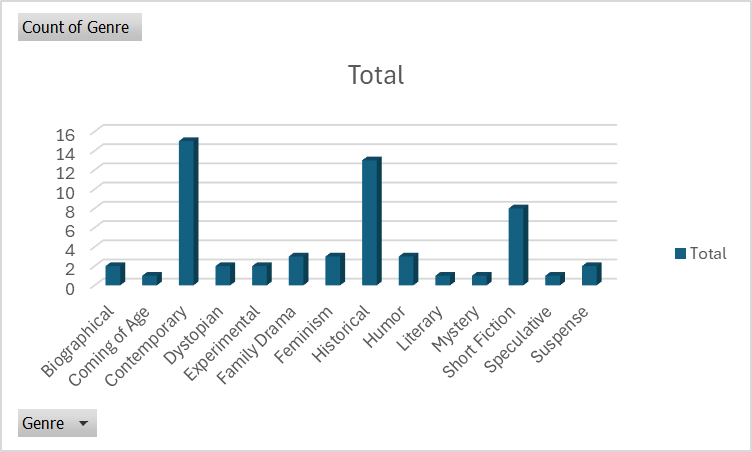

Genres

This section is problematic, I know, but I decided to add it at the last moment. The problem is that genres are so fluidly described these days that I could have a different list for each book! I tried for broader categories and used a search when I needed to, but sometimes I got as definitive a genre as “novel.” I also realize that short fiction could also fit into one or more of these genres, but I didn’t go there. I didn’t want to deal with specifying more than one genre per book. So, I did my best. Here is the genre breakdown I came up with. I was surprised by how many of the novels were historical, although I know it has recently become a very popular genre.

How Much I Liked Them

I wasn’t sure how to organize this section, so I decided to break it up into categories by how much I enjoyed the book. So, with no more adieu . . . These books are ordered by year of the prize, with the earliest first. For the most part, you will see that the category I put a book in has no relationship to whether it won that year or not. Winners are marked in red.

Books I Loved

- Wolf Hall by Hillary Mantel (2010)

- The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet by David Mitchell (2011)

- The Invisible Bridge by Julie Orringer (2011)

- All the Birds, Singing by Evie Wyld (2014)

Books I Highly Recommend

- The Children’s Book by A. S. Byatt (2010)

- Solace by Belinda McKeon (2012)

- Snowdrops by A. D. Miller (2012)

- The Panopticon by Jenni Fagan (2013)

- Benediction by Kent Haruf (2014)

- Dear Thief by Samantha Harvey (2015)

- Fourth of July Creek by Smith Henderson (2015)

- The Wolf Border by Sarah Hall (2016)

- The First Bad Man by Miranda July (2016)

- The Lesser Bohemians by Eimer McBride (2017)

- American War by Omar El Akkad (2018)

- White Tears by Hari Kunzru (2018)

- Demon Copperhead by Barbara Kingsolver (2023)

Books I Moderately Recommend

- The Selected Works of T. S. Spivett by Reif Larsen (2010)

- There But for the by Ali Smith (2012)

- The Big Music by Kirsty Gun (2013)

- The Deadman’s Pedal by Alan Warner (2013)

- Harvest by Jim Crace (2014)

- In the Light of What We Know by Zai Haider Rahman (2015)

- We Are Not Ourselves by Matthew Thomas (2015)

- A Country Road, A Tree by Jo Baker (2017)

- Attrib. and Other Stories by Eley Williams (2018)

- Heads of the Colored People by Nafissa Thompson-Spires (2019)

- Sight by Jessie Greengrass (2019)

- Ducks, Newburyport by Lucy Ellman (2020)

- Sudden Traveler by Sarah Hall (2020)

- Travelers by Helon Habila (2020)

- Girl by Edna O’Brien (2020)

- Alligator & Other Stories by Dimi Alzayat (2021)

- A Children’s Bible by Lydia Millet (2021)

- LOTE by Shola von Reinholdt (2021)

- Memorial by Bryan Washington (2022)

- Bitter Orange Tree by Jokha Alharthi (2023)

So-So or Even Meh or Some Good Stuff

- Strangers by Anita Brookner (2010)

- Nocturnes by Kazuo Ishiguro (2010)

- The Lotus Eaters by Tatjana Soli (2011)

- Leaving the Atocha Station by Ben Lerner (2013)

- The Flame Throwers by Rachel Kushner (2014)

- You Don’t Have to Live Like This by Benjamin Markovits (2016)

- Beatlebone by Kevin Barry (2016)

- What Belongs to You by Garth Greenwell (2017)

- First Love by Gwendolyn Riley (2018)

- The First Woman by Jennifer Nunsubuga Makumbi (2021)

- English Magic by Uschi Gatward (2022)

- Libertie by Kaitlin Greenidge (2022)

- A Shock by Keith Ridgway (2022)

- Bolla by Pajtim Statovci (2023)

- After Saphho by Shelby Wynn Schwartz (2023)

Books I Actively Disliked or That Annoyed Me

- La Rochelle by Michael Nath (2011)

- You & Me by Padgett Powell (2012)

- The Sport of Kings by C. E. Morgan (2017)

- Murmur by Will Eaves (2019)

- Crudo by Olivia Laing (2019)

Best and Worst

The best book choice is tough, but I pick Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel. It captured me every second and was minutely researched.

The worst book choice is easy, the only one I didn’t finish, You & Me by Padgett Powell. Who needs to rewrite Waiting for Godot anyway? And so unfunny.