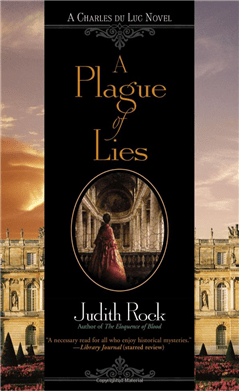

A Plague of Lies is the third in the mystery series set in 17th century France and featuring Charles du Luc, a master of rhetoric at the Louis le Grand school in Paris.

A Plague of Lies is the third in the mystery series set in 17th century France and featuring Charles du Luc, a master of rhetoric at the Louis le Grand school in Paris.

Charles is dismayed when he is summoned to escort Père Jouvancy to the court at Versailles to present Madame de Maintenon with the gift of a holy relic. Madame is angry with the Jesuits because the King’s confessor, Père la Chaise, convinced the King not to give her the title of Queen, so the gift is an attempt to regain favor. Although Charles disapproves of what he sees as the Sun King’s constant self-glorification, he must escort Père Jouvancy, an old man who is just recovering from an illness that is raging through Paris.

On their way to Versailles, Charles and Jouvancy encounter Lieutenant-Général de la Reynie, head of the Paris police, whom Charles has assisted on occasion. La Reynie asks Charles to keep an eye on the Prince of Conti while he is there and to listen to what is said about him.

Once at court, though, Père Jouvancy has a relapse, and Charles comes close to witnessing the death of a much-disliked man, the Comte de Fleury. Apparently, he too was ill and running for the latrine when he slipped on the wet floor and fell down the stairs. The rumor is that he was writing a scandalous memoir, and poison is immediately mentioned. When the other members of Charles’ party fall ill, there are more rumors of poison, but all the men seem to just have food poisoning.

De Fleury does appear to have been poisoned, however, and Charles observes several people going in and out of his room, including the Duc du Maine, son of the King. Charles finds himself getting embroiled in the problems of the Duc’s sister, Mademoiselle de Rouen, who is soon to be engaged to the son of the King of Poland and is not happy about it. Charles also observes Conti behaving suspiciously. Next, a gardener is found drowned.

The novel presents us with a convoluted plot but also with a fascinating portrait of the court at Versailles. Rock’s knowledge of the period, even of how the places she describes would have appeared at that time, seems convincingly complete. Her novels are always absorbing.