It’s always fun to re-read Nancy Mitford’s charming and funny autobiographical novel about her youth and young womanhood. Mitford’s alter ego is Linda, a young woman with terrible taste in men, who throws herself from one extreme to another in pursuit of love.

It’s always fun to re-read Nancy Mitford’s charming and funny autobiographical novel about her youth and young womanhood. Mitford’s alter ego is Linda, a young woman with terrible taste in men, who throws herself from one extreme to another in pursuit of love.

Mitford’s strength is her portrayal of peculiar but lovable characters, all modeled upon her own eccentric family or on figures in society. The novel is narrated by Fanny, a sensible but lonely girl who spends a lot of time with her cousins, the Radletts. Her terrifying Uncle Matthew (modeled on Mitford’s father) loves to hunt his children instead of foxes, a game the children love. Aunt Sadie is unutterably vague, which she probably has to be to live with Uncle Matthew. Uncle David is a cultured hypochondriac. The Bolter, Fanny’s mother, is supposedly a portrayal of Lady Idina Sackville, a famous society woman who kept leaving her husbands and was a member of Kenya’s famous Happy Valley set.

Mitford starts the novel with childhood–the children are hunted, hang out in the linen cupboard fantasizing about running away, and generally run wild–and follows the older girls into young adulthood. The novel finally centers on the story of how Linda first impetuously marries a stuffy banker who bores her silly, then leaves him for a communist who only thinks about his causes, and finally falls into the arms of Fabrice, a French duke who is a world-class womanizer. Characterized by facetious observations of society life and dialogue brimming with zingers, Mitford’s novel is a joy to read.

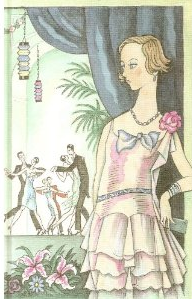

Just as an aside because I’ve recently read a few posts about cover design, I originally copied into this post the most recent cover of the book, which shows a romantic black and white photo of a debutant holding a bouquet of flowers with a pink banner for the title. I decided to replace it with this older cover (the one on the copy I have), which I think does a much better job of conveying the type of novel it is, much more of a social commentary than a romantic novel.