I sometimes feel frustrated with modern short works because I want them to tell more. Unlike short stories from earlier times, they don’t close any loops but simply capture a moment. This statement explains why I prefer the novel form and may not be very avant garde in my tastes.

I sometimes feel frustrated with modern short works because I want them to tell more. Unlike short stories from earlier times, they don’t close any loops but simply capture a moment. This statement explains why I prefer the novel form and may not be very avant garde in my tastes.

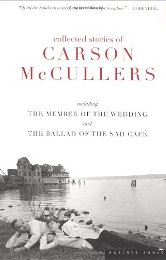

Collected Stories of Carson McCullers contains a large number of short stories–some set in New York and some in the south–and two longer works, “The Ballad of the Sad Café” and “A Member of the Wedding,” only the last of which I had read before.

McCullers captures mostly sad moments, many of them autobiographical from what I understand from the introduction. Three of the stories are about her marriage to an alcoholic, although in one it is the wife who drinks.

Although McCullers is known as a “Southern Gothic” writer, the only piece in this collection that truly fits that description is “The Ballad of the Sad Café.” This story illustrates her ideas about love–that people love other people who are unattainable and that even the most unlikely people can be the recipients of adoration or even obsession. Several of the other stories are also about this theme.

“A Member of the Wedding” explores the unhappy adolescent, also one of McCullers’s themes. Frankie, a 12-year-old girl, becomes fixed on the idea that when her brother marries his fianceé they will take her with them on their honeymoon. She is obsessed with this idea and won’t allow herself to admit that they probably won’t. Her obsession is ultimately rooted in the degree to which she hates her town and herself.

Readers familiar with McCullers do not expect cheerful tales, but they are beautifully written and evocative.