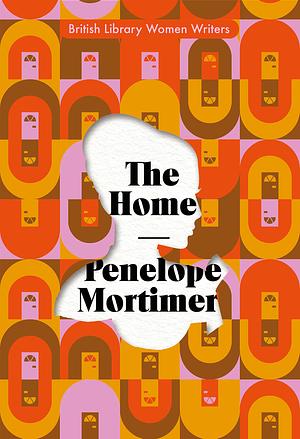

Eleanor is moving. She’s doing this because after 26 years of marriage, her husband is leaving her. Their marriage had been an open one, which translated to her husband Graham being serially unfaithful while she had two affairs that ended in friendship because she loved Graham. The last few years have not been happy, but still it’s hard for her to accept that he has left her—without really talking about it—for a woman who is younger than her oldest daughter.

Now she is trying to make a home for children who, all but one, are adults living on their own. Nevertheless, they return in ones and groups to stay with her.

Eleanor struggles in this novel with the idea of what home is, with loneliness, with her desire to mother children who don’t really need it anymore, with desire and love for Graham, and with the need for someone to take care of her. The novel looks unflinchingly at the situation that many middle-aged women found themselves in beginning in the 1970’s, when divorce rates began to rise. For example, Graham (who in my opinion is an unrelenting jerk) supposes Eleanor can get a job when she has been trained for nothing and has no work experience for the last 26 years except being a wife and mother.

This is sometimes a rough read but always an insightful one. Mortimer has an unfailingly observant eye.