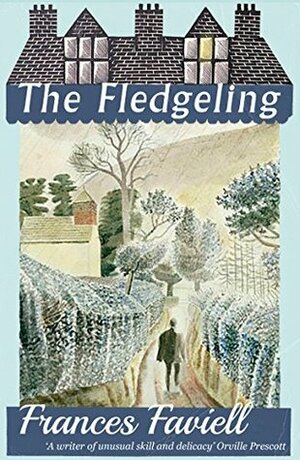

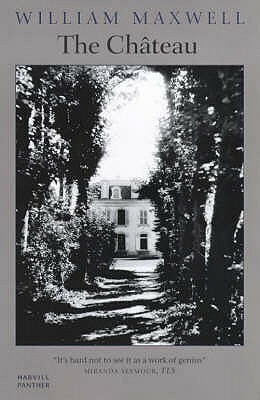

When World War II broke out in France, Hilary Wainwright left his pregnant wife Lisa in Paris to rejoin his regiment, thinking that the British would be fighting in France. He only saw his son, John, once, shortly after he was born. Later, he heard that Lisa, who was working with the resistance, was dead. He had no idea what happened to the baby, but he once received a visit from Pierre Verdier, the fiancé of Lisa’s best friend, Jeanne. He reported that Lisa had given the baby to Jeanne shortly before she was arrested, but that now Jeanne was dead, and he did not know what happened to the baby.

The war is over, and Pierre returns. He tells Hilary he wants to look for John for him. Hilary is now ambivalent about finding his son. When Lisa was killed, he envisioned getting comfort from raising his son, but it has been five years. Now he’s more worried about how to tell whether any boy they find is really his.

Pierre eventually traces a boy who might be John to a Catholic orphanage in Northern France. Hilary goes to Paris to meet the people Pierre traced. He has always loved France, but post-war, the country is in dire straits. Hilary travels to the northern town to try to determine whether the boy, called Jean, is his.

Frankly, I disliked Hilary pretty much all the way through this novel. The Afterword says that it takes Hilary until the last few pages to know his own mind, but in fact, he uses every excuse to try to disassociate himself from responsibility. When he thinks he would be betraying Lisa if he accidentally took home the wrong boy, for example, it seems clear from what is said about her that she would have taken Jean as soon as she saw his plight.

Small spoiler—when it seemed Hilary was going to use his lust for an obvious slut to break his promises, I was really disgusted.

That being said, I still enjoyed reading this novel, which is touching and insightful into human weakness. It also provides a post-war view of France that is bleak and that I hadn’t read of before.