Best Book of the Week!

Best Book of the Week!

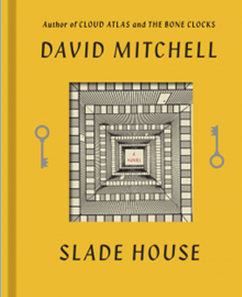

I haven’t read any ghost stories lately, so David Mitchell’s Slade House will have to do for a first nod to Halloween. Fans of Mitchell know to expect something unusual from his work, and Slade House is no exception. This novel features a series of characters over five decades all about to set foot in the mysterious Slade House.

Nathan Bishop, a nerdy teenager perhaps on the autism spectrum, is on his way with his mother down Slade Alley looking for Slade House. In the alley they meet a workman and ask him directions. He has never heard of it. They find the small iron gate leading into the gardens, and the workman is the last person ever to see them.

Nathan has taken a little of his mother’s Valium, so he thinks the drug is affecting his vision when the scenery in the Slade House garden fades. But something more sinister is happening while his mother is in the house attending a concert.

It’s difficult to say much more about this novel without revealing too much. Suffice it to say that people are in peril and the suspense builds accordingly. The book is divided into six sections, beginning in 1979, with each one set nine years further on. Each time a person is drawn into the house, never to be seen again.

Readers of Mitchell will pay attention in the last section when the name Marinus is mentioned, for they know that a few of the same characters appear in his books, sort of. Let us say that characters with the same names appear in his books. Slade House continues the complex story of horologists that came to the fore in The Bone Clocks.

Readers of Mitchell will pay attention in the last section when the name Marinus is mentioned, for they know that a few of the same characters appear in his books, sort of. Let us say that characters with the same names appear in his books. Slade House continues the complex story of horologists that came to the fore in The Bone Clocks.

As usual with Mitchell’s books, Slade House reflects exciting writing, a complex back story, a large creep factor, and a battle between good and evil. What more could you want?