The city of New Venice floats on the ice in the Arctic Circle in this steampunkish work of fantasy fiction. The city is a supposed near-utopia, not a utopia because it is ruled by the corrupt Council of Seven and their sinister police force, the Gentlemen of the Night. The residents of the city dress in Victorian clothing and go on about their business, which is most often the pursuit of pleasure (and their idea of pleasure, basically sex and drugs, also doesn’t fit into my idea of a utopia). A black airship hangs over the city, but no one seems concerned about it.

The city of New Venice floats on the ice in the Arctic Circle in this steampunkish work of fantasy fiction. The city is a supposed near-utopia, not a utopia because it is ruled by the corrupt Council of Seven and their sinister police force, the Gentlemen of the Night. The residents of the city dress in Victorian clothing and go on about their business, which is most often the pursuit of pleasure (and their idea of pleasure, basically sex and drugs, also doesn’t fit into my idea of a utopia). A black airship hangs over the city, but no one seems concerned about it.

The novel has two main characters, friends. Brentford Orsini is an aristocrat, an administrator of the city gardens, and a friend to the frightening Scavengers. He is concerned about the behavior of the Council of Seven, particularly in its mistreatment of the Inuit, and has anonymously published a subversive pamphlet called “A Blast on a Barren Land.” Gabriel d’Allier is more of a bohemian, concerned with his own pleasure. He is a reluctant professor at the city college who is being pushed out by the machinations of a colleague and his accusations of impropriety with students. He also soon finds himself receiving the unwelcome attentions of the Gentlemen of the Night, who think he knows who wrote the pamphlet.

Brentford receives a visit from a ghost in his dreams, Helen, a former lover, who tells him to make a trip to the North Pole. He heads out the morning after his disappointing wedding. Gabriel, who has ruined Brentford’s wedding and is in despair about his own love affair, sets out on his own intending to freeze to death outside the city’s controlled Air Architecture.

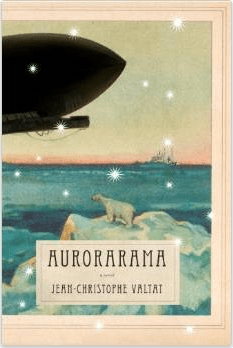

At this point, the novel, which is imaginative and well written in a style that is faintly Victorian (and has, as you can see, a beautiful cover—yes, I got it for its cover), becomes one of the silliest books I have ever read. It is almost hallucinogenic at times, like a combination of watching a side show and taking too many drugs. I can imagine it developing some kind of cult following, but I found it exceedingly ridiculous.

At one point when the book describes Snowdrift and Reliance, a book being read by one of the characters, I felt the description could have been self-referential, just substituting Victorian for Elizabethan:

Part melodrama, part Elizabethan tragedy, Snowdrift and Reliance has little to recommend it to the reader’s benevolence, the bewildering intricacies of its plot being further shrouded by unfathomable esoteric symbolism, not to mention an amphigoric style whose only coherent trait is its consistent lack of taste.