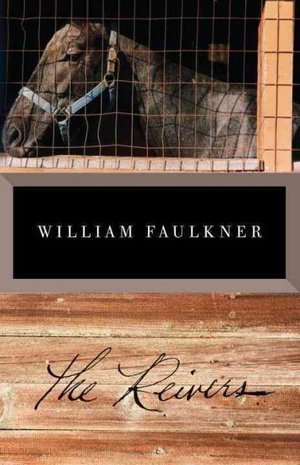

The Reivers is William Faulkner’s last novel, written in 1962, which I chose as my last selection for the 1962 Club. Unlike some of his more famous novels, it is told straightforwardly by its main character, Lucius Priest, as a grandfather telling a yarn about his childhood to his grandson. I believe Faulkner wrote this novel, which reminded me of Huck Finn, for pure fun.

Key to the story, which is set in 1904 when Lucius is 11, is Boon Hoggenbeck, an overgrown man-child who works for Lucius’s grandfather, referred to as Boss. Lucius’s grandparents and parents have no sooner departed for the funeral of Lucius’s other grandfather than Boon decides to take Boss’s brand new automobile and Lucius to Memphis, both sort of colluding in this misbehavior without actually discussing it. On the way there, they discover that Ned, Boss’s Black coachman, has hitched a ride with them by hiding under a tarpaulin.

In these early days of cars in Mississippi, the trip to Memphis is in itself an adventure, but things heat up when Boon delivers himself and Lucius to a whorehouse (although Lucius calls it a boarding house) where Boon has a favorite girl, Miss Corrie.

A bunch of colorful characters appear, including Otis, a boy described as having something wrong and who you don’t notice until it’s almost too late. But the story really kicks in when the miscreants learn that Ned has traded Boss’s automobile for a horse that he plans to race against another horse that already beat it twice.

I wasn’t sure this was going to be my kind of story, but mindful of the time (it is definitely not politically correct in so many ways), and I mean 1904 not 1962, it is funny and contains some philosophizing about right and wrong.