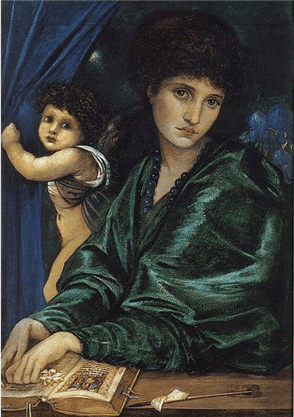

I received this book in a First Reads giveaway from Goodreads. I haven’t read Naslund before, so I am not sure whether she adapted her writing style for this novel, but it took me awhile to accustom myself to it. She follows the activities of two artists, one Kathryn Callaghan, a fictional older writer in the current time, and the other a once-living person, Élisabeth Vigée-Le Brun, a painter known especially for her portraits of Marie Antoinette.

I received this book in a First Reads giveaway from Goodreads. I haven’t read Naslund before, so I am not sure whether she adapted her writing style for this novel, but it took me awhile to accustom myself to it. She follows the activities of two artists, one Kathryn Callaghan, a fictional older writer in the current time, and the other a once-living person, Élisabeth Vigée-Le Brun, a painter known especially for her portraits of Marie Antoinette.

The modern-day story begins at midnight next to a fountain of Venus in a neighborhood of Louisville, Kentucky. Kathryn, or Ryn, is taking her newly finished manuscript to her friend Leslie’s door because she can’t wait to deliver it.

The novel’s structure is a book within a book. Chapters following one day in Ryn’s life are interleaved with chapters covering the whole of Vigée-Le Brun’s life, which are from Ryn’s book. Both stories are about the theme of what it means to be an artist and what you must give up of your personal life to pursue your profession. The novel is said to be a deliberate variation on Joyce’s Portrait of an Artist as a Young Man, but it has been so long since I’ve read it that I cannot comment on that.

This novel is contemplative, especially in the modern-day narrative, but the interleaving of stories in such short chapters slows down the pace too much. It literally takes until page 34 for Ryn to walk across the street and deliver the manuscript. Even with some chapters from the 18th century interleaved, the pace is frustrating. I found myself thinking, when is this woman going to make it across the street?

I found the story of Vigée-Le Brun’s life more compelling than the modern-day story, during which we follow Ryn’s every thought. She is an excitable, emotional woman who contemplates everything she looks at and repeatedly broods over the same things. We read about the russet and yellow fall colors or the appearance of the fountain many times. Nothing much happens all day until a late-night confrontation that seems artificially created to provide some tension.

I did not feel, however, that the two women, Ryn and Vigée-Le Brun, were two different people–they seemed to be the same person in different time periods. Vigée-Le Brun is slightly less emotionally excitable than Ryn, but their observations of the world around them, their attention to color and the details of design and structure, are very similar. Vigée-Le Brun’s narrative style, in first person where Ryn’s is in third person, is a little more formal as befitting an earlier age, but conversations in this story often sound stilted, and her first conversation with Marie Antoinette is positively sycophantic.

Naslund’s writing style, although sometimes vibrant and lyrical, often seems affected, particularly in the modern-day story. The copy I read was an advanced reader’s edition and it had quite a few typos, which I assume will be corrected. I was not quite as sure of some self-consciously unusual phrases, whether they were stylistic choices rather than errors. Naslund’s writing style tends to the unusual, to be sure, but I stumbled over some of these phrases. The only one I wrote down was an instance where some characters “made quick chat.”

I wanted to like this novel more than I did. I think the theme of women and art is worth exploring, although I’m not sure how much this novel actually explored this issue, despite its obvious intentions. I am actually curious about the alleged feminist leanings of Naslund and their effect on this book. Vigée-Le Brun has to put up with her father and then husband appropriating all her money and, in her husband’s case, only giving her a bit of it back as an allowance. When they divorce, he gets almost everything. Yet, she is determined not to let it bother her. I am not sure whether that is a feminist viewpoint or not.

However, the characters in this novel certainly reflect the “gift for pleasure” noted in reviews of Ahab’s Wife (which I am currently reading). The women go on pursuing their lives and dreams without much heed to their menfolk, they have cordial relations with those around them, they delight in color and the fineness of life. Their regrets and sorrows mostly focus on their children.

One thing that surprised me about the historical story was that Vigée-Le Brun hardly seemed to notice the causes of the French revolution or the revolution itself. There is one scene where a woman confronts her on the street and another where she grieves for the fate of so many. That’s about it.

Conversely, it is hard to believe that she would be shocked to the core by seeing a model of internal organs, as artists had been studying the body for hundreds of years. I do not know how much of this novel actually reflects Vigée-Le Brun’s true thinking and feeling. The danger when portraying a historical person is that you are imagining who the person really is–you don’t know–and you have no idea if you are doing them justice or injustice.

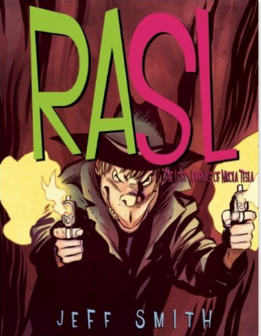

Every once in a while, I dabble in graphic novels, without really knowing much about them. I’m not at all interested in the violent or superhero ones that seem to dominate the genre but in the more unusual ones. This volume of RASL pulled me in with its reference to Nikola Tesla. Tesla is one of my husband’s interests, so I picked it up at the library to read together.

Every once in a while, I dabble in graphic novels, without really knowing much about them. I’m not at all interested in the violent or superhero ones that seem to dominate the genre but in the more unusual ones. This volume of RASL pulled me in with its reference to Nikola Tesla. Tesla is one of my husband’s interests, so I picked it up at the library to read together.