When I was younger, I used to confuse John le Carré and Ken Follett, but last year I went to see the excellent movie Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. After that, I began reading le Carré again (my review of the novel is here) and have realized that he is the real spellbinder.

When I was younger, I used to confuse John le Carré and Ken Follett, but last year I went to see the excellent movie Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. After that, I began reading le Carré again (my review of the novel is here) and have realized that he is the real spellbinder.

Although le Carré writes about espionage, these are not your typical James Bond novels. Le Carré is interested in the moral ambiguity of the work and in psychological drama rather than action. Nevertheless, his novels are extremely suspenseful.

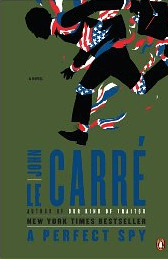

At the beginning of A Perfect Spy, Magnus Pym has escaped his bosses in the British government and the Americans who are investigating him and has arrived at his secret rooms in a small British seaside town to write his novel, he says. As the British search for him feverishly and his boss Jack Brotherhood reluctantly begins to wonder if he is the traitor the Americans claim, Pym writes the sad story of his life.

Pym’s father has recently died, and Pym feels himself finally free to be himself, but perhaps even Pym doesn’t know who he is. His story begins with his charismatic father–a man who is beloved by many but who is also a liar, a cheat, a con man, and a thief. Pym learns to lie and pretend everything is fine from a master, and he goes on pretending for his entire life. But Pym’s motivating force, unlike his father’s, is never money. It is love. He will be anyone and do anything to make people love him.

Is Pym a traitor or isn’t he? As his boss and his wife frantically try to find him, Pym recalls the circumstances and tangled events that lead him to where he is in the present time, alone in his rooms contemplating the next step.

It is difficult to convey, without giving much away, just how compelling this novel is. Le Carré’s genius is that he can make you care for this deeply flawed character and keep you riveted by his story. A Perfect Spy is said to be the most autobiographical of le Carré’s books. It is certainly an involving novel.