As much as I have enjoyed other novels by Halldór Laxness, I just couldn’t get into World Light. I think it was its allegorical qualities that put me off, as that is not my genre.

As much as I have enjoyed other novels by Halldór Laxness, I just couldn’t get into World Light. I think it was its allegorical qualities that put me off, as that is not my genre.

Olaf Karason is a foster child who has been brought up on a remote Icelandic farm. He is so badly treated there that in his teenage years he takes to his bed as an invalid. He is sadly aware of his own history, in which his father abandoned him, and his mother sent him away in a bag. He hears she is now doing well, but she shows no interest in him.

Olaf has a spiritual turn of mind and believes he has experienced some knowledge of God. He also wants to be a poet and is hungry for knowledge. But to the people surrounding him, this all just makes him seem more peculiar. He is almost ridiculously innocent, too, and because of his innocence and his hunger for love, he keeps thrusting himself into situations where he is misunderstood.

While Olaf is on the farm, I stayed with him, but more than 100 pages into the book, he loses his home and the parish sends a man to fetch him. That man, Reimar, takes him to a farm where he is miraculously cured before taking him to his destination in a convalescent home. But Olaf is cured, so no one knows what to do with him.

This section seemed to begin an entirely different book, and here it started to lose me. Because I felt as if I didn’t understand something, I began to read the Introduction, something I usually don’t do before finishing a novel, if then. Unfortunately, that told me enough about what was coming for Olaf that I developed a sense of dread. I struggled on but finally decided to stop.

Laxness’s novel is apparently an indictment of all the forces in the world against gentler souls. Certainly, the social climate and behaviors he depicts are brutal. As with some of his other novels, I had to keep reminding myself that it was set in the 20th century, because it seems to be several centuries earlier.

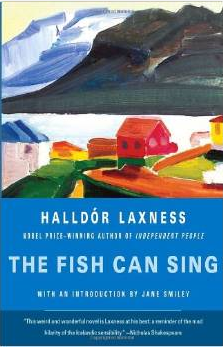

I hope my review doesn’t stop anyone from reading Laxness. Generally, I find him wonderful, with a keen, dark sense of humor. If this doesn’t sound like your kind of book, try Independent People (my personal favorite of the ones I’ve read) or Iceland’s Bell.