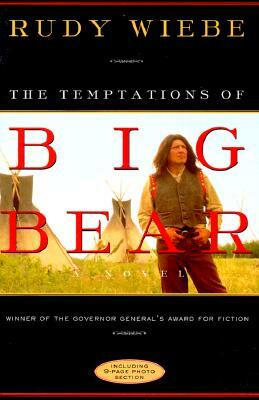

Again, when I finished reading this book, which was supposed to be for my A Century of Books project, I found the year already occupied. I have been using Goodreads and often Wikipedia to find books for each year, but Goodreads seems particularly inaccurate. I suspect that what happened here was that it listed the novel for, say, 1981, where I still have a hole (as of this writing in February), because of a 10-year anniversary reprint. I often check the dates if they seem suspicious, but this one didn’t. It’s especially bad now because it took eight days to read, and I am way behind on my reading. I only have a few more books to go, but from now on, I’m double-checking the publication date before I start reading.

Lyman Ward, a former academic just in his 50s, has contracted a bone disease that has frozen his neck so that he can’t turn it, confined him to a wheelchair, and resulted in the amputation of one of his legs. He is almost completely helpless, so his son wants to move him into care, but he stubbornly remains in his grandparents’ home in Grass Valley, California, being taken care of by Ada, a local woman.

His wife, Ellen, left him abruptly for his surgeon when he was helpless in the hospital. Although her partner died soon after and she has shown signs of wanting to return, he stubbornly refuses to see her.

Lyman can read, though, and do other sedentary activities. He was raised by his grandparents, and his grandmother was in her time a famous illustrator and writer, Susan Burling Ward. He has come across newspaper clippings and letters she wrote to her best friend, so he decides to write a biography of her, partly to answer questions for himself about events in his family he doesn’t understand.

Angle of Repose combines Lymon’s current experience and thoughts as he does this work with the events in the biography he is writing. The historical arc of the novel predominates, so much so that I occasionally wondered why Lyman’s story was there at all. However, by the end I understood how his grandparents’ history informs his own.

It’s a mismatch. Susan Barling as a young woman is from Upstate New York, a gifted artist just beginning to become known. She yearns for a life of culture. Her best friend, Augusta, comes from a prominent, cultured New York City family, and as young women, Susan and Augusta make a threesome of friends with Thomas Hudson, a poet and editor who goes on to become famous himself. She meets Oliver Ward, a young mining engineer, when she is very young. Unlike her other friends, he is taciturn and maybe too respectful of them all. He goes away on a job in the West for five years.

Thomas, sensitive, intelligent, and delicate, is Susan’s idea of a perfect man. He picks Augusta, though, and Oliver returns around the same time. Despite her friends’ misgivings, Susan decides to marry Oliver. Her idea is that Oliver can get some experience in the West and then move back East to live a more cultured life. She doesn’t seem to realize that to do his work, he must be in the West, and he is suited for that life.

As far as his career is concerned, Oliver seems too prone to consult Susan’s convenience, and she has unrealistic ideas. He turns down some opportunities because they don’t seem suitable to Susan. He takes a short-term job and they live apart. (She is too genteel for these rough mining camps.) She finally joins him near a mining town named New Almaden, southeast of San Jose. He has taken a house away from town, which anyway she removes herself from, as she does everywhere they live, thinking herself too good for the company. As Lyman says, his grandmother is a snob. Here she begins a pattern of not joining into society and their life but enduring it.

The couple doesn’t thrive financially. At this time, there are lots of qualified engineers available and most of them aren’t as fussy about where they’ll go. Susan’s work writing articles about the West and illustrating other writers’ work is helping support them, despite Oliver’s dislike of the situation and Susan’s complaints about it. They move to Leadville, Colorado, which although it is primitive, allows her to open her home to some intelligent visitors and have lively, informed discussions, which she loves. But the Leadville mine eventually grinds to a halt because of a lawsuit brought by would-be claim jumpers.

The couple goes to Mexico, which Susan loves, but the mine doesn’t prove promising. Their projects gain and then lose funding, and so on.

Susan writes to Augusta constantly, but Augusta never acknowledges Oliver as a fit husband. I fear that much of Susan’s growing disappointment has to do with wanting to justify her choice to her friends.

In the novel’s current time (the late 1960s and early 70s), Lyman expresses some irritating views on the times and young people. I wasn’t sure whether they were Stegner’s own views or more delineation of Lyman’s character, but Lyman eventually forms a sort of friendship with a young woman who acts as his secretary for a time.

This is ultimately a fascinating and absorbing story, but this time through (I apparently read it in the mists of time but didn’t remember anything about it) I kept getting distracted from it. I’m not sure why. I think, though, that it deserved more attention from me. Although I was bothered by Lyman seeming to blame all his grandparents’ problems on his grandmother (and after unfortunate events, his grandfather’s intransigence), the novel is considered Stegner’s masterpiece and won him the Pulitzer.

Related Posts

Obscure Destinies

The Town

North Woods