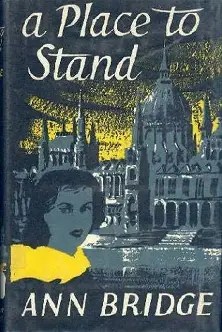

The first novel I read by Ann Bridge was contemplative. This one becomes much more action oriented. But both are about women developing new conceptions of themselves. This one is about a young woman becoming an adult.

A Place to Stand was published in 1951, but it is set ten years earlier. Hope Kirkland is a little bit spoiled, a nineteen-year-old American whose wealthy father is an oil executive living in Budapest for the last eight years. Although she and her mother have lived there that long, neither of them seems to understand much about what’s going on around them politically.

Hope is engaged to Sam Harrison, a young journalist who has just been transferred to Istanbul. At his departure, he gives Hope a large box of chocolates, which she thinks is an odd goodbye gift. However, when she opens it, she finds it contains two passports for young men and money with a note of where to take them. So, she does. In a less desirable neighborhood, she finds a group of Polish refugees, an old woman, her two sons Jurek and Stefan, and Jurek’s fiancée Litka.

Hungary is neutral, but Poland is fighting the Nazis. Some Hungarian politicians are pushing the country toward Germany, so Polish refugees are in potential danger. Stefan and Jurek are almost ready to leave the country, but they are waiting for something to arrive from Poland first.

Hope is immediately drawn into the affairs of the Polish group. She is struck by what was clearly once a wealthy family having no home and no possessions. Then the Nazis arrive in Budapest and immediately begin looking for Poles. At the same time, the Americans are asked to leave the country.

I had to get over my initial reaction to Hope and her general obliviousness, which was made worse for me by Bridge’s continual use of the word “little” to describe just about everything about her, her little hand, her little figure, etc. However, this novel turns into an adventure that results in self-discovery for her. I enjoyed it quite a bit, acknowledging that probably many rich American girls at the time were silly and clueless (although ones living right there in Budapest? I’m not so sure).