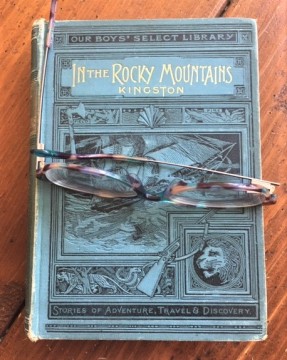

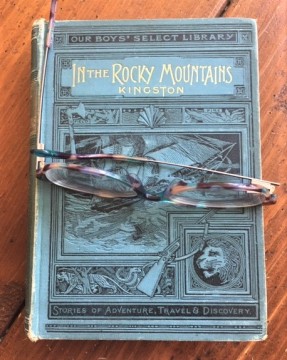

Quite a few years ago, I bought an old 19th-century boys’ adventure book, On the Banks of the Amazon by W. H. G. Kingston. In reading it, I was struck by its combination of adventure, interesting information about plants, animals and natives of the area, and engraved illustrations. As a result, I put together a small collection of these books from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, trying to find ones in the Our Boys’ Select Library edition of the first one. (In case you’re wondering why there is a ship and a lion on the cover of a book about the Rockies, they all have the same cover.) I intended to read them all but never got to any of the others. Then when we moved to Washington, they got lost.

Quite a few years ago, I bought an old 19th-century boys’ adventure book, On the Banks of the Amazon by W. H. G. Kingston. In reading it, I was struck by its combination of adventure, interesting information about plants, animals and natives of the area, and engraved illustrations. As a result, I put together a small collection of these books from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, trying to find ones in the Our Boys’ Select Library edition of the first one. (In case you’re wondering why there is a ship and a lion on the cover of a book about the Rockies, they all have the same cover.) I intended to read them all but never got to any of the others. Then when we moved to Washington, they got lost.

That was four years ago, and a few months ago my husband finally unearthed them from an unpacked box of his books. He brought In the Rocky Mountains up to show me, and I decided to read it.

Before the action of this book, Ralph and his sister Clarise were on their way west with their parents to start a new life, but both their parents died en route. Their wagon train was rescued by a group of men, and one of them turned out to be their Uncle Jeff, who had gone west years before and not been heard of again. Now, Ralph and Clarice, Clarice’s servant Rachel, and Uncle Jeff and his men live on a commodious ranch in the foothills of the Rockies, and Uncle Jeff and his men help supply settlers coming through the nearby pass.

A friendly native named Winnemak comes to warn them that a large band of “Arapahas” (by which I assume he means Arapahos) and Apaches have banded together (did they ever, I wonder) and plan to attack their compound. At first, Uncle Jeff is unworried, but the ranchers, along with a small group of cavalry, are overcome and must flee into the wilderness.

Most of this action is designed to lead us to Yellowstone, for the pass to the fort is overtaken by the enemy, so Ralph and his companions must go north, where they end up stranded for the winter in Yellowstone Valley. This leads us into descriptions of the wonders of Yellowstone.

This novel was published in 1901, a good 20 years after the other one I read, and I fear it isn’t quite as good. For one thing, although I try not to judge books by their times, there is a good deal more judgmental treatment of the indigenous peoples than in the book about the Amazon even though it is mixed with having some “good” native characters (which is of course defined by their friendliness to the “harmless” whites). It also expresses an uncritical affirmation of Manifest Destiny, containing a statement (sorry, I didn’t mark the passage to be able to quote directly) that the white men were doing nothing more than trying to get themselves some land when viciously attacked by the natives.

Okay, so maybe all that is to be expected, as well as the stereotypical treatment of the African-American servant and the Irish and German soldiers. On the other hand, the friendly natives express themselves in fluent and educated English, which is surprising for this book, with the exception of saying “Ugh!” as a greeting. (Did they really do that, do you think?)

A fairly minor error is made in illustrating and naming various deer Ralph sees. He talks about seeing wapiti, which is another name for elk, but the illustration is more like a standard deer. Then he clearly describes and illustrates a moose but calls it an elk. Oh dear. As far as I know, those names are not interchangeable. (A friend tells me now that this may be a mismatch between American names for these animals and British ones; however, the book is set in the U. S., so I think it should use the American names.)

I think the thing that for me interfered most with this adventure was a strong Christian message that comes through especially at the end. Ralph and Clarice convert Winnemak from his wicked ways, with no acknowledgment that these peoples have their own beliefs and religion that are just as valid, and Winnemak becomes a missionary. Ugh, as they (don’t) say. I can only suspect that as Kingston got older, he felt compelled to add a moral message. I don’t remember anything like that in On the Banks of the Amazon and I hope I don’t see it in the others, which I still intend to read.

I wrote my review a few months ago, and since then I read an old copy of Walter Scott’s The Talisman, also marketed as a boys’ book and published in 1907. I was really interested to notice in the advertising pages at the back of the book a title In the Heart of the Rockies by G. A. Henty, which appears to have at least a partially identical plot to W. H. G. Kingston’s book only calls its hero Tom instead of Ralph. I looked to see if the names were pseudonyms of the same writer, and they were not. The Kingston book was published a few years before the Henty book, so I’m wondering if a little plagiarism wasn’t going on.

Related Posts

The Loon Feather

Treasure Island

Immortal Wife