Best Book of the Week!

Best Book of the Week!

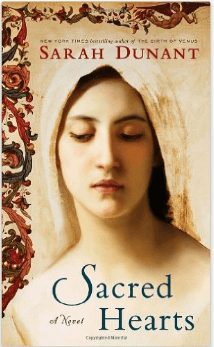

Sacred Hearts is another book I read for my Walter Scott Prize project. Although Sarah Dunant is an author I’ve read in the past with moderate enjoyment, I very much enjoyed her novel about the Borgias, Blood & Beauty.

This novel is also set in Renaissance Italy, in 1570 Ferrara. Dunant begins the book by telling us that in the second half of the 16th century, dowries had become so expensive that roughly half the daughters of noble families were consigned to convents, whether willingly or unwillingly.

Suora Zuana is one of that number. When her professor father died years before, she had nowhere to go and her dowry was small. Yes, dowries had to be paid to convents as well, but they were much smaller than those paid with brides.

Her small dowry has not earned Zuana very many comforts in the convent of Santa Caterina, but she has created a valuable role for herself as a healer and dispenser of remedies. She has managed to bring along many of her father’s books, although some of the most valuable were stolen at his death by his students and peers, and she has greatly expanded the convent’s herb garden. Aside from caring for the convent’s ill, she makes medicines for the bishop and others.

At the opening of the novel, she is on her way to drug Serafina, a novice who has been screaming for days, ever since she was forcibly ensconced in the convent by her family. She is a girl from Milan, so no one in the convent is familiar with her family. Suora Zuana is able to calm her, and later they find she has an angelic voice, which delights the convent choir director.

For the sake of everyone’s peace, the abbess, Madonna Chiara, asks Suora Zuana to take Serafina under her wing rather than handing her over to the novice mistress, Suora Umiliana. So, Zuana begins teach Serafina how to prepare medications. None of the sisters know that Serafina has hatched a plot to escape from the convent with her lover, the musician Jacopo.

What Serafina doesn’t understand, although she probably wouldn’t care, is that this is a politically delicate time for Santa Caterina and for all convents in general. Reforms on the heels of the Counter-Reformation have resulted in a cracking down on convents in some cities. Madonna Chiara fears that the convent’s few liberties will be lost, especially if they have a scandal. Their means of making a living will be removed, their orchestras disbanded and performances disallowed, their books will be confiscated, and they will no longer be allowed outside in the garden. Visitors will only be able to see them behind a grating. This is what has been happening throughout Italy.

On the local front, some of the sisters, led by Suora Umiliana, would like the convent to become stricter in its observances, even though it is already strict. Suora Umiliana is a religious zealot who is fascinated by Suora Magdalena, the convent’s “living saint.” Although Suora Magdalena has long been close to death, when she was younger she had fits of ecstasy and suffered from stigmata. Shortly after Serafina arrives at the convent, Magdalena has the first of her fits in years and speaks to Serafina. Later, when Serafina becomes ill, Umiliana thinks she can use her condition to take over control of the convent from Chiara.

Although I was interested in this novel, it took me some time to become really involved in it. I am revealing more about the plot than I usually would, because the description of the book from the blurb about how Suora Zuana comes to care for Serafina does little to convey the depths and power of this novel. For quite a while I had no idea where it was going and wondered how interested I was, but the novel turned out to be very much worth reading. This is one that really sneaks up on you.

Related Posts

Blood & Beauty

The Malice of Fortune

The Chalice

In 1939 Paris after the German occupation, Sid Griffiths and the members of the Hot Time Swinger’s American Band have just finished cutting a record when Hiero Falk, German but black, is picked up by the Gestapo and never seen again. In 1992, Falk, now considered a jazz legend on the basis of that one recording of the “Half-Blood Blues,” is being honored with the opening of a documentary in Berlin. Sid quit playing years ago, but Chip Jones, another member of the band, talks him into attending.

In 1939 Paris after the German occupation, Sid Griffiths and the members of the Hot Time Swinger’s American Band have just finished cutting a record when Hiero Falk, German but black, is picked up by the Gestapo and never seen again. In 1992, Falk, now considered a jazz legend on the basis of that one recording of the “Half-Blood Blues,” is being honored with the opening of a documentary in Berlin. Sid quit playing years ago, but Chip Jones, another member of the band, talks him into attending.